How to Do Powder Coating with Laser Engraving? (Using xTool D1)

Posted by XTOOL ONLINE STORE

The vast majority of people with laser engravers tend to view powder coating as something to get rid of. It's on all sorts of metal objects that folks want to customize, such as tumblers.

A few years ago, I came across an advertising video for a commercial laser engraver. What caught my attention was that the focus of the video was not removing powder coating specifically, but, removing it and replacing it with a different color. Replace it not with paint, but with more powder coating. I ended up filing that in the back of my noggin, and only recently sat down and took the time to figure it out.

How does Power Coating Work?

How powder coating is done is fairly simple. Basically, a static charge is applied to a metal object. Like a balloon that's been rubbed on your head, the static charge creates an attraction. Powder coating media, a very fine plastic dust is then blown towards the object.

The field of attraction draws in the dust, so that it sticks to the object's surface. Once covered, the coated object is baked, causing the media to melt and adhere to the metal, forming a strong outer layer.

Can a Laser Engraver Coat Powder?

For a laser engraver, providing the heat to melt the media is easy enough. That's what it does anyhow. But a laser beam is tiny, ruling out melting media in mass quantities all at once. The attraction between material and media doesn't exist. Quite the opposite, as common laser modules blow soot, dust, and smoke around by design.

And then there is the usage aspect. Engraver owners are using mostly non-metal materials, or metal objects they are using cannot be cut into by a common blue diode laser. Those owners want to add color on a smaller scale, color which flows with the material or sticks to the top of the material.

Let’s figuring out how to get around the process issues that I set out to do. But before that, this is a challenging technique to get right, and not suggested for beginners who struggle with the basics of operating a laser engraver.

Adhesion Problem

It didn't take long to figure out that simply melting powder coating media wasn't going to work everywhere. My initial test materials included ceramic tiles, glass, and wood. The wood mostly did ok, but you could pick at the powder coating and get it to come off again. So, decorative, but not functionalities.

Glass and ceramic were much worse. It didn't take much effort at all to get the melted media to come off. The thing is, powder coated metal is rough, not smooth, which gives the media plenty of nooks and crannies to get into and hold on with.

With this in mind, I got out some 80-grit sandpaper and roughed up the material. Bam! We got stick! But the exposed material looked awful, rather than something one would be making a product from, and sanding was tedious. Selectively sanding would have been even more tedious. How to selectively rough up material?

Making a Pocket Using Laser

Hey, we have a laser, don't we? And what exactly does it do? It vaporizes and removes material! And it doesn't leave behind a smooth surface if we don't want it to. Running one's finger over a lasered surface, the roughness left behind can be felt. And, we can also use the laser to dig into some materials, carving away some of it.

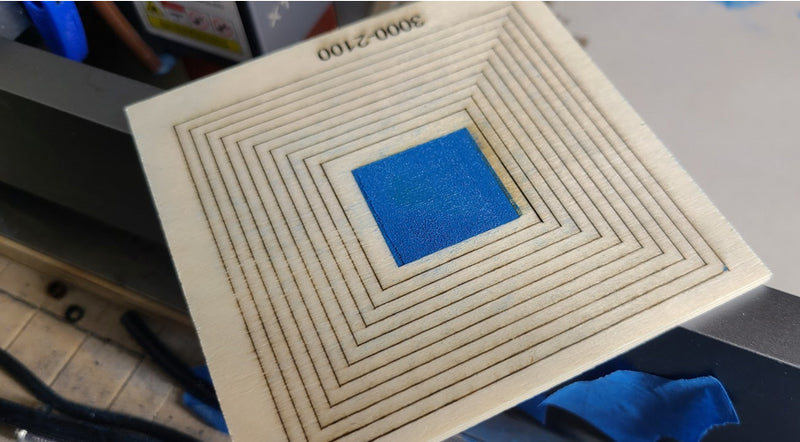

That would give us two things at one time - a rough surface and an indentation in the material which can be filled with melted media so that it can be level with the surface. A pocket.

To make a suitable pocket, we need to know the power and speed combination that will get us where we want to be. To find this out, we use a power speed test. These are commonly used to work out which combination of power and speed will get you the color engraving you want at the fastest speed.

But experienced owners know that they can tell you much, much more. In this case, it can tell you the combination needed to get the pocket depth you want.

For wood, a high-speed test is usually best to start with. For materials like ceramic, a low-speed test will be better, as you have to destroy the hard finish.

Glass is somewhere between, and may need a masking material, same as if you're etching on it. The color of the glass will also come into play, as dark glass doesn't necessarily need any masking at all.

Position Precision of Laser Head and Material

If we're going to use the laser to selectively rough up the material by making pockets, then we are going to need to be able to get the laser right back to the exact same spots later, after we have filled the pockets with powder coating media. (And we're not even going down the road of framing so the artwork is where it's supposed to be on the material.)

That's a problem for any engraver that doesn't have limit switches or some other method for getting the laser back to within less than a mm. Even slightly off is going to be noticeable.

For me, it can still be off 1-2mm. Typically, that's not noticeable or I work around it. But in this case, that wasn't going to work. Thankfully, a really cool guy named Joe designed a manual homing jig.

In brief, you home your machine, use the jig to set the laser module's position, and go. By using this jig, you'll be able to hit the same spot with very high precision, every single time. If you have a different method that works for you, keep on using it.

One last thing here. With the laser able to hit accurately every time, that leaves the material. That can't move either. And with what we'll be doing later, assuming you can hold the material with your fingers is asking for heartbreak. Secure your material so it can't move. I use painter's tape, all the way around.

Application of Media

Now comes the fun part. The beginning of the mess, as we fill the pockets with media. More or less, get yourself a little scoop of media, and gently dump it onto your material. Remember, a little goes a long way.

There are two goals here. First, the pockets are full of media. Second, the media is tamped down into the pockets so the media at the bottom is squished in the roughed-up material. If wanting the media to be even with the material surface, that will be a third goal.

One way to accomplish this is to use something semi-rigid to act as a spatula and sweep. After much trial and error, what I found worked best for me was a metal business card. It can sweep, scoop, and be used to squish.

This allows me to move the media around, get into the pockets, pack it down, level it out, and then move any excess off the material onto something that can transfer it back to its container. Why waste it? Let's be clear, the material is not going to be completely clean. We'll fix that later.

For what it's worth, another method I tried included adding it to water and airbrushing it on. Not so good, lots of waste, and clogged the brush frequently. Making a paste was tried, but it needed to dry and knowing when it was fully dry was hit and miss. If used on wood, the wood had to dry too, adding further complications. Do please experiment, maybe you'll find a better method!

Best Settings for Laser Powder Coating

The ever-present question, "What settings did you use?" And the standard response, "I ran a power speed test and picked the one I thought looked best." I ran this first to see what settings would get me the pocket depth I wanted.

Next, I modified the test grid to use the combination picked for every box in the grid, which set up the material for the final run to find out which settings to use for melting the media nicely without charring it. It's that simple. Generally speaking, it doesn't take a whole lot of power, so speeds can be pretty high.

How to Prevent the Laser Module Fan from Blowing Powder Away?

"But didn't the fan on the laser module blow away the powder?" It would have, yes. And in my initial experiments, it did. There isn't a great workaround for this part yet. What I did to solve this was crude but effective - I blocked up the fan's intake just before hitting the go button and unblocked it as soon as the job finished.

This is not something one normally does with a laser, and can lead to the laser going into thermal shutdown because it gets too hot. To see how this would go, I installed a thermocouple on the module and watched the temperature while the laser was doing its work. In 5min, the temp had risen 5C, so about 1C per minute.

Other options here would be to create a duct to capture the fan's exhaust and send it elsewhere instead of straight down. As of this writing, I don't know if anything like that exists, so you'll have to be clever and figure something out, wait until someone else is clever and copy them, or block the fan.

Getting Good Results

Not going to kid you, it took some doing to hammer out this process. And I expect it will take you some trial and error as well. There isn't a sure-fire-always-works-perfectly set of instructions for something this nuanced.

It's more complicated than editing and dialing in settings for a photograph, which is also very nuanced. It's going to take practice. One nice thing is, as long as you do not move the material, you can run the job again if the first run didn't work out right.

More Tips

When the media melts together, all the air between the dust particles is removed, causing the level of the material to drop.

In the above case, you can add more media to the pocket and run again, and again, and again.

Don't get greedy adding extra passes, as there is a fine line between just a tad low and way too much.

Too much media will drown out small details, blurring them together.

Using this on a rotary is likely going to be more mess than it's worth unless you've come up with some way to make the media stick to the material while being rotated.

Powder Cleanup

This is pretty easy. All the media dust that wasn't lasered is still dust. I would pick up my finished piece, turn it sideways over a piece of paper, and then tap the material on the paper a few times to get the media off. That can go back into the container with the rest for another day.

You'll probably still have some stuck on the material, especially if it's wood. Compressed air takes care of this, but be mindful that you don't want to be breathing this stuff.

A non-metal brush can help, as well as a vacuum with a brush attachment. Once all the excess is gone from the material, clean up any powder still hanging around in the work area.

Tutorial Takeaway

Step 1: Make sure you have a solid method for getting the laser module to the exact same position every time you run a job.

Step 2: Use a power speed test to rough up your material and determine depth of pockets needed for powder coating media.

Step 3: Use power speed test to determine media melt point desired.

Step 4: Secure material to the bed.

Step 5: Create pockets in material.

Step 6: Spread and pack pockets with media.

Step 7: Remove excess media.

Step 8: Melt media in pockets with laser.

If results unsatisfactory, repeat steps 5-7.

Step 9: Clean up remaining excess media.

Enjoy your triumph!

This tutorial is orginally written by Cobey Schmidt, a proud xTool D1 owner, and is published by xTool with full authorization.

Feel free to subscribe to Cobey's YouTube Channel if you find this post inpiring and helpful to your creation.

SHARE: